In 1956 a group of young painters in Denmark decided to overcome the obstacles to get their works seen by renting a venue and make their own group exhibition. That was against the unwritten rules, which were to not form a group before all the members had been accepted several times at one of the official, censored exhibitions.

Our group consisted of six painters and two textile artists and the first years were quite successful.

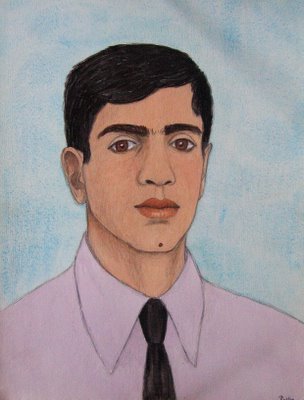

The second year only half of the group showed, but we kept the name. Here I am, second from right:

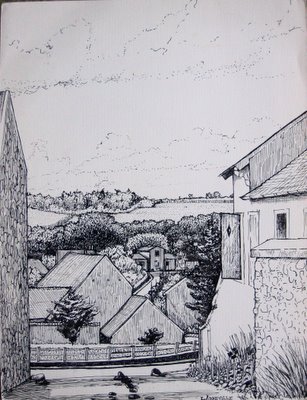

The third year the art critic from the newspaper Information wrote a rather rude negative article about us and we decided to respond. We used his own words, but supplanted our name with his. It clearly brought out the quality of personal insult in his writing and we laughed uproariously while we composed it. The paper published it and the next day a sour reply from the critic who of course got the last word. He got more than that. Next year he came to our exhibition at the same time as two other critics and they had a conference right under our eyes. The day after, all three papers brought similar negative evaluation of our efforts and the number of visitors was in the one digit range with no sales at all. That became the end of our venture.

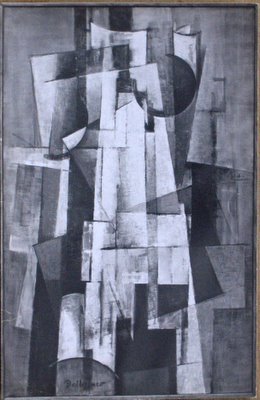

I made this satirical drawing of the critic’s conference:

Ole Strøygård, who was the most idealistic in our group, had another idea. “Let us make a censored exhibition where we let in all the young talents who are rejected by the others,” he said. That was the start of ‘Sommerudstillingen’ (The Summer Exhibition). Ole wanted us to keep in the background, so we chose a committee of six young painters to censor the works while we were doing the manual labor of carrying paintings back and forth. The first day we saw several good painters being denied and some inferior ones being accepted. The next day Ole took the committee to task and confronted them with their choices from the previous day. They had to admit that they were too conservative and after that day they changed their judgments and the resulting exhibition was sensational. Even this triumph was not to continue. Both of the official censored exhibitions opened up for all the best painters from ‘Sommerudstillingen’, which lost its ammunition and died after the second year. Still, we were happy enough with what we had achieved, it had blown a fresh wind into Danish art.

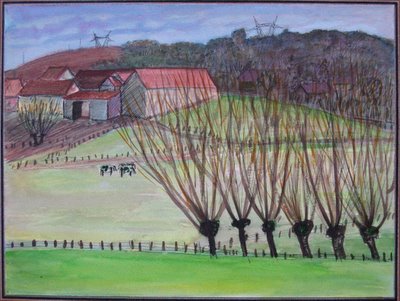

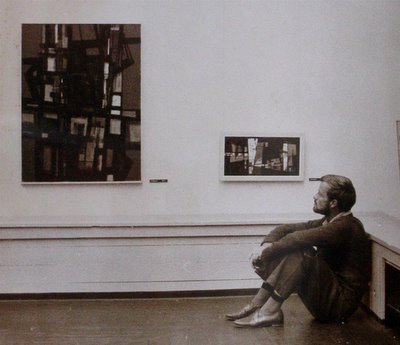

Here I am contemplating a couple of my paintings.

Here I am contemplating a couple of my paintings.