In the religious and medical traditions of Asia, the human person was said to have three sources of energy: sexual, breath, and spirit. Sexual energy is what you spend during sexual intercourse. Breath energy is the kind of energy you spend when you talk too much and breathe too little. Spirit energy is energy that you spend when you worry too much, and do not sleep well. If you spend these three sources of energy, your body is not strong enough for the realization of the Way and a deep penetration into reality. Buddhist monks observe celibacy, not because of moral admonition, but for conservation of energy.

(Thich Nhat Hanh, ‘Being Peace’, Parallax Press, Berkeley, CA, 1987, p.100-101)

Sunday, July 30, 2006

Friday, July 28, 2006

Thursday, July 27, 2006

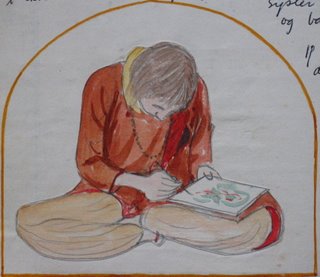

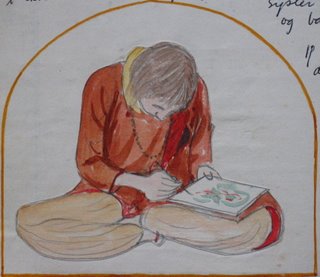

Painting a Thanka

Wednesday, July 26, 2006

Live in the Spirit (a quote)

Live in the spirit, say the grandfathers; the spirit never will demand a surrender of your reason or deny you any urge. Whoever says that man shall suspend his reasoning looks for ways of stifling the spirit, and whoever says that man shall repress his natural desires hunts ways for killing joy.

From Ruth Beebe Hill's ‘Hanta Yo’ (Clear the Way), An American Saga.

From Ruth Beebe Hill's ‘Hanta Yo’ (Clear the Way), An American Saga.

Tuesday, July 25, 2006

Monday, July 24, 2006

JOURNEY TO THE EAST 8

Back in Bodhanath I decided to go and see Bhagawan Dass, but when I came to Kopan he was not home. I was about to leave when a tall handsome American woman with a crew cut and dressed in Tibetan robes called me back.

“I am Zina,” she said, “but you can call me mother! What are your plans?”

“I am soon going back to India,” I said.

“That is not a good idea,” she said. “The rainy season is unbearable, it is too hot. You should stay here, the monsoon is very pleasant here.”

“But my visa is running out.”

“I can help you with a visa.”

“But I have no money.”

“I can help you with money, and you can stay here for free. I’ll give you a room and money every month.”

She took me round to the secluded south side of the house and showed me a large airy room. “This is the best room, it just needs to be cleaned, then you can stay here. And you can meet the Lamas; they are not here now, but they are coming soon.”

This is how I came to stay at Kopan.

When I arrived a week later my room was not yet ready and Zina asked me I if I would mind sharing a room with Michael a few days. “Michael is in silence,” she said, “and it will only be a couple of days anyway!”

Michael Hollingshead, a baldish and bearded hippie about my age, was actually trying to kick a heroin habit, and he was not ready to be silent. From the moment I became his roommate he made use of my voice; he was constantly writing notes asking me to tell the cook this and ask Zina that. When I came back from a trip to Katmandu, quite exhausted, he had spread his papers all over the room, and there was hardly space to sit down, let alone to rest. The days passed without my room being ready, and I was about to give up, but I had read a word by the Buddha: “If you are not able to live with demons, you cannot find enlightenment.” Finally after five days I lost my patience and called on Zina: “Michael is driving me crazy, you have to get my room ready tomorrow.” Michael was angry that I had complained, but at least that made him stop writing notes, and the following day I got my room and peace was restored.

The rainy season went by quietly. The weather was pleasant; it didn’t rain too much, often just a short violent storm late in the afternoon that left the air fresh and balmy. Zina gave me small artistic jobs to do for her, and it felt good to finally settle down. I started sewing handbags with embroidery in Tibetan style to sell. The promised money from Zina did not always show up, but with board and lodging free I didn’t need much.

When the rains stopped the lamas arrived. Geshe Thubten Yeshe and Thubten Zopa Rimpoche, as they were introduced by Mother Zina - whom nobody ever called Mother. She liked to give names. She referred to me as ‘our Babaji’, and Babaji became my name. On Thubten Yeshe she conferred the title of Geshe though he had not actually taken the Geshe degree, which is like a doctorate. He was 35 years old, and at first he just seemed to be another extremely friendly Tibetan, as all the ones I had met on my trek had been. Thubten Zopa was young and good-looking and his whinnying laughter sounded ever so often. We all had our meals together, and I soon came to feel very comfortable with Thubten Yeshe whose down-to-earth manner fitted well with my Taurean nature.

When the rains stopped the lamas arrived. Geshe Thubten Yeshe and Thubten Zopa Rimpoche, as they were introduced by Mother Zina - whom nobody ever called Mother. She liked to give names. She referred to me as ‘our Babaji’, and Babaji became my name. On Thubten Yeshe she conferred the title of Geshe though he had not actually taken the Geshe degree, which is like a doctorate. He was 35 years old, and at first he just seemed to be another extremely friendly Tibetan, as all the ones I had met on my trek had been. Thubten Zopa was young and good-looking and his whinnying laughter sounded ever so often. We all had our meals together, and I soon came to feel very comfortable with Thubten Yeshe whose down-to-earth manner fitted well with my Taurean nature.

“I am Zina,” she said, “but you can call me mother! What are your plans?”

“I am soon going back to India,” I said.

“That is not a good idea,” she said. “The rainy season is unbearable, it is too hot. You should stay here, the monsoon is very pleasant here.”

“But my visa is running out.”

“I can help you with a visa.”

“But I have no money.”

“I can help you with money, and you can stay here for free. I’ll give you a room and money every month.”

She took me round to the secluded south side of the house and showed me a large airy room. “This is the best room, it just needs to be cleaned, then you can stay here. And you can meet the Lamas; they are not here now, but they are coming soon.”

This is how I came to stay at Kopan.

When I arrived a week later my room was not yet ready and Zina asked me I if I would mind sharing a room with Michael a few days. “Michael is in silence,” she said, “and it will only be a couple of days anyway!”

Michael Hollingshead, a baldish and bearded hippie about my age, was actually trying to kick a heroin habit, and he was not ready to be silent. From the moment I became his roommate he made use of my voice; he was constantly writing notes asking me to tell the cook this and ask Zina that. When I came back from a trip to Katmandu, quite exhausted, he had spread his papers all over the room, and there was hardly space to sit down, let alone to rest. The days passed without my room being ready, and I was about to give up, but I had read a word by the Buddha: “If you are not able to live with demons, you cannot find enlightenment.” Finally after five days I lost my patience and called on Zina: “Michael is driving me crazy, you have to get my room ready tomorrow.” Michael was angry that I had complained, but at least that made him stop writing notes, and the following day I got my room and peace was restored.

The rainy season went by quietly. The weather was pleasant; it didn’t rain too much, often just a short violent storm late in the afternoon that left the air fresh and balmy. Zina gave me small artistic jobs to do for her, and it felt good to finally settle down. I started sewing handbags with embroidery in Tibetan style to sell. The promised money from Zina did not always show up, but with board and lodging free I didn’t need much.

When the rains stopped the lamas arrived. Geshe Thubten Yeshe and Thubten Zopa Rimpoche, as they were introduced by Mother Zina - whom nobody ever called Mother. She liked to give names. She referred to me as ‘our Babaji’, and Babaji became my name. On Thubten Yeshe she conferred the title of Geshe though he had not actually taken the Geshe degree, which is like a doctorate. He was 35 years old, and at first he just seemed to be another extremely friendly Tibetan, as all the ones I had met on my trek had been. Thubten Zopa was young and good-looking and his whinnying laughter sounded ever so often. We all had our meals together, and I soon came to feel very comfortable with Thubten Yeshe whose down-to-earth manner fitted well with my Taurean nature.

When the rains stopped the lamas arrived. Geshe Thubten Yeshe and Thubten Zopa Rimpoche, as they were introduced by Mother Zina - whom nobody ever called Mother. She liked to give names. She referred to me as ‘our Babaji’, and Babaji became my name. On Thubten Yeshe she conferred the title of Geshe though he had not actually taken the Geshe degree, which is like a doctorate. He was 35 years old, and at first he just seemed to be another extremely friendly Tibetan, as all the ones I had met on my trek had been. Thubten Zopa was young and good-looking and his whinnying laughter sounded ever so often. We all had our meals together, and I soon came to feel very comfortable with Thubten Yeshe whose down-to-earth manner fitted well with my Taurean nature.

Sunday, July 23, 2006

Saturday, July 22, 2006

Friday, July 21, 2006

Friday Night

Melanie making up. The house is glowing and warm in the summer night.

Melanie making up. The house is glowing and warm in the summer night. My two housemates are ready for Friday night.

My two housemates are ready for Friday night. I stay home and technically babysit with a monitor. But the kids have been properly tired out and there is not a sound to be heard from them.

Tonight I worship the green Goddess, Purveyor and Protector of Dreams manifest in Beauty.

I am listening to Aziza, the group I was studying with in Africa in 02. It rocks! Their music, which takes material from different tribes in Ghana, has wonderful singing and mesmerizing drums. I have danced to some of these rhythms.

And then I am blogging;

I think blogger-thoughts;

I think about the connection with you my friends and readers who tell me from time to time that you are visiting here; I thank you!

And thank you to you who just drop in!

And thank you to you who have commented - (that's you, Sue ;-)

I must concede that I don't leave many comments with others, so I guess I don't deserve them.

Talking blogger-talk is a sign that one has been infected with bloggeritis.

JOURNEY TO THE EAST 7

(Scroll down to read the previous accounts of the Journey to the East)

It was my plan to trek in the high mountains before my return to India. Torben took a photo of our departure showing Tove and Jytte walking with a group of barefoot sadhus in orange robes, from left: Fut, Niels Ebbe, Hurtigkarl who cannot be seen except for his feet, Tove, me with a big basket à la Newari, Jytte and John. Most of them were seeing us off, only Niels Ebbe and Hurtigkarl was going on the trek; both of them I hardly knew, and Niels Ebbe I didn’t particularly like, but they were not going as far as I, who had planned to reach Junbesi, the first Sherpa village in a valley. A few days out we were sitting in a small settlement when we spotted a figure coming down the trail. It was a tall blond boy dressed in a white dhoti and with a crown of dreads. “Bhagawan Dass,” said Niels Ebbe. In ‘Be Here Now’ by Ram Dass I had read about Bhagawan Dass; the boy that set Richard Alpert on his path and brought him to his guru, and I had heard that he was around. It is always an occasion when you meet another traveler out in the mountains, and we ordered tea and sat smoking and talking for a couple of hours until we had to continue each his way. Bhagawan Dass said to come and see him when I returned, he was staying at Kopan, and when he described how to get there, I recognized the hidden house on the hill.

A few days out we were sitting in a small settlement when we spotted a figure coming down the trail. It was a tall blond boy dressed in a white dhoti and with a crown of dreads. “Bhagawan Dass,” said Niels Ebbe. In ‘Be Here Now’ by Ram Dass I had read about Bhagawan Dass; the boy that set Richard Alpert on his path and brought him to his guru, and I had heard that he was around. It is always an occasion when you meet another traveler out in the mountains, and we ordered tea and sat smoking and talking for a couple of hours until we had to continue each his way. Bhagawan Dass said to come and see him when I returned, he was staying at Kopan, and when he described how to get there, I recognized the hidden house on the hill.

After a few more days my companions turned around, and I was on my own. The path went over ridge upon ridge. In the valleys lived the Hindus, but on top of the ridges I began to come upon Sherpa settlements. The Sherpas have been in the high parts of the Nepali Himalayas for the last 2-300 years. They migrated from Tibet and their language, culture, and religion are still Tibetan. Finally, in Junbesi, even the bottom of the valley is so elevated that the Sherpas have settled here. I stayed with a family for a few days and did a trek up the valley to the famous monastery Thubten Chöling. It is a beautiful lush valley, and it has a homey feeling for a Scandinavian person. When I began my trek home a little servant boy from the family I had stayed with caught up with me and insisted on following me. He had a tough life and I had been kind to him, so he had decided to throw his lot in with me. The next day he began to get doubts, and when we met a man from Junbesi he agreed to return with him.

I had been walking barefoot all the way and had constant trouble with my feet. On the way back I also got a stomach infection and could not keep anything in me. I felt weak, but there was no alternative, I had to go on. The last day, on the way slowly up the last ridge, I met an American who gave me a bag of trail mix. That proved to be the first food that didn’t go right through me, and it gave me good energy so that I strode along the ridge and arrived at the paved road with my stomach back in order and my feet tough and for the first time without any sores.

It was my plan to trek in the high mountains before my return to India. Torben took a photo of our departure showing Tove and Jytte walking with a group of barefoot sadhus in orange robes, from left: Fut, Niels Ebbe, Hurtigkarl who cannot be seen except for his feet, Tove, me with a big basket à la Newari, Jytte and John. Most of them were seeing us off, only Niels Ebbe and Hurtigkarl was going on the trek; both of them I hardly knew, and Niels Ebbe I didn’t particularly like, but they were not going as far as I, who had planned to reach Junbesi, the first Sherpa village in a valley.

A few days out we were sitting in a small settlement when we spotted a figure coming down the trail. It was a tall blond boy dressed in a white dhoti and with a crown of dreads. “Bhagawan Dass,” said Niels Ebbe. In ‘Be Here Now’ by Ram Dass I had read about Bhagawan Dass; the boy that set Richard Alpert on his path and brought him to his guru, and I had heard that he was around. It is always an occasion when you meet another traveler out in the mountains, and we ordered tea and sat smoking and talking for a couple of hours until we had to continue each his way. Bhagawan Dass said to come and see him when I returned, he was staying at Kopan, and when he described how to get there, I recognized the hidden house on the hill.

A few days out we were sitting in a small settlement when we spotted a figure coming down the trail. It was a tall blond boy dressed in a white dhoti and with a crown of dreads. “Bhagawan Dass,” said Niels Ebbe. In ‘Be Here Now’ by Ram Dass I had read about Bhagawan Dass; the boy that set Richard Alpert on his path and brought him to his guru, and I had heard that he was around. It is always an occasion when you meet another traveler out in the mountains, and we ordered tea and sat smoking and talking for a couple of hours until we had to continue each his way. Bhagawan Dass said to come and see him when I returned, he was staying at Kopan, and when he described how to get there, I recognized the hidden house on the hill.After a few more days my companions turned around, and I was on my own. The path went over ridge upon ridge. In the valleys lived the Hindus, but on top of the ridges I began to come upon Sherpa settlements. The Sherpas have been in the high parts of the Nepali Himalayas for the last 2-300 years. They migrated from Tibet and their language, culture, and religion are still Tibetan. Finally, in Junbesi, even the bottom of the valley is so elevated that the Sherpas have settled here. I stayed with a family for a few days and did a trek up the valley to the famous monastery Thubten Chöling. It is a beautiful lush valley, and it has a homey feeling for a Scandinavian person. When I began my trek home a little servant boy from the family I had stayed with caught up with me and insisted on following me. He had a tough life and I had been kind to him, so he had decided to throw his lot in with me. The next day he began to get doubts, and when we met a man from Junbesi he agreed to return with him.

I had been walking barefoot all the way and had constant trouble with my feet. On the way back I also got a stomach infection and could not keep anything in me. I felt weak, but there was no alternative, I had to go on. The last day, on the way slowly up the last ridge, I met an American who gave me a bag of trail mix. That proved to be the first food that didn’t go right through me, and it gave me good energy so that I strode along the ridge and arrived at the paved road with my stomach back in order and my feet tough and for the first time without any sores.

Thursday, July 20, 2006

Abortion (a quote)

Abortion is sometimes necessary, sometimes not, always sad. It is to the woman as war is to the man – a living sacrifice in a cause justified or not justified, as the observer may decide. It is the making of hard decisions – that this one must die that that one can live in honor and decency and comfort. Women have no leaders; a woman’s conscience must be her General. There are no stirring songs to make the task of killing easier, no victory marches and medals handed round afterwards, merely a sense of loss.

(Fay Weldon, ‘The Hearts and Lives of Men’, p.65)

(Fay Weldon, ‘The Hearts and Lives of Men’, p.65)

Wednesday, July 19, 2006

Tuesday, July 18, 2006

Monday, July 17, 2006

Sunday, July 16, 2006

JOURNEY TO THE EAST 6

In the spring of 1970 I went to Nepal with an old friend, the Danish photographer Torben Huss. We went by Varanasi where we spent a day, then by train to the Nepalese border. Here we were looking for a ride with a truck and were shown where to ask in a store. There was a flock outside; two Americans were complaining and whining: “You said you were going at ten. Now it is noon; when are you going?” - “Why don’t you keep to the agreement?” - “How long is it going to last?”

The rest of the flock was listening, and so were we. The drivers sat on the floor working on a tire and they didn’t even look up. Finally the Americans gave up and left, and the crowd dispersed. When we were the only ones left, we asked if they were going to Katmandu, and they said, yes, they were leaving soon, and, yes, we could get a ride.

It was a glorious ride; most of the way we sat on top of the drivers cap while the heavily loaded truck ground up the winding road through the shining mountains. We reached the top as the sun went down and passed the night on the ground next to the truck.

Next morning we arrived in Katmandu and Torben, who had been there in the early sixties, just after Nepal was opened for travelers, could not recognize the town, so many new buildings had grown up. We found the mini-bus to Bodhanath that is not far from Katmandu. Where we got off the bus, there were a few houses along the road.

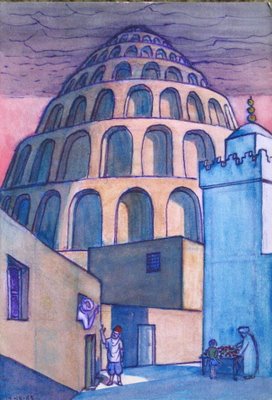

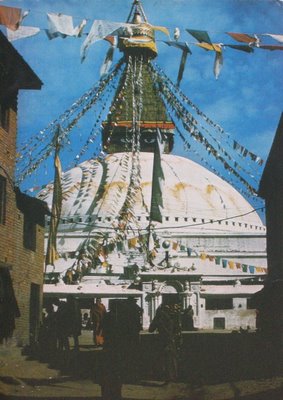

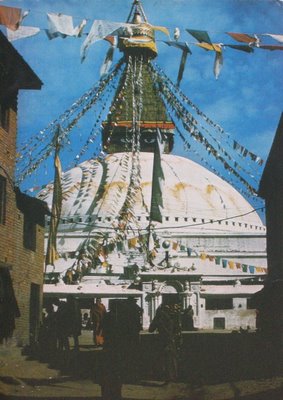

Between two of them an opening lead in to the gigantic stupa whose golden upper part was decorated with the serene eyes of the Buddha. The stupa was surrounded by one circle of houses, and this was the whole town of Bodhanath. Monks and nuns and lay Tibetans were circling the stupa, keeping it on their right side; some had prayer wheels, others were turning the prayer wheels that were set in the wall all the way around. We circled a couple of times and went through a narrow passage on the opposite side from the road and came out on a path through the rice fields. After a few minutes walk we found John’s house where we were going to stay.

Between two of them an opening lead in to the gigantic stupa whose golden upper part was decorated with the serene eyes of the Buddha. The stupa was surrounded by one circle of houses, and this was the whole town of Bodhanath. Monks and nuns and lay Tibetans were circling the stupa, keeping it on their right side; some had prayer wheels, others were turning the prayer wheels that were set in the wall all the way around. We circled a couple of times and went through a narrow passage on the opposite side from the road and came out on a path through the rice fields. After a few minutes walk we found John’s house where we were going to stay.

Looking from the house, away from the stupa towards the mountains in the north, there was a small hill with a flat top with two great trees. Just as Sidi Ali had called me when I was in Meknès, this hill called me now, and one day, when I was smoothly coming down from an acid-trip, I obeyed the call. With brisk energy I completed the half hour walk up there before the sunset. I sat by a small shrine on the west side and saw the sun set behind the glittering golden towers of Katmandu showing the hill of Swayambunath in silhouette. Before leaving I looked around. There was a marvelous view of the whole valley from the top of the hill, and on the south side I found a half open gate, through which I spied an old house, hiding behind tall hedges.

The rest of the flock was listening, and so were we. The drivers sat on the floor working on a tire and they didn’t even look up. Finally the Americans gave up and left, and the crowd dispersed. When we were the only ones left, we asked if they were going to Katmandu, and they said, yes, they were leaving soon, and, yes, we could get a ride.

It was a glorious ride; most of the way we sat on top of the drivers cap while the heavily loaded truck ground up the winding road through the shining mountains. We reached the top as the sun went down and passed the night on the ground next to the truck.

Next morning we arrived in Katmandu and Torben, who had been there in the early sixties, just after Nepal was opened for travelers, could not recognize the town, so many new buildings had grown up. We found the mini-bus to Bodhanath that is not far from Katmandu. Where we got off the bus, there were a few houses along the road.

Between two of them an opening lead in to the gigantic stupa whose golden upper part was decorated with the serene eyes of the Buddha. The stupa was surrounded by one circle of houses, and this was the whole town of Bodhanath. Monks and nuns and lay Tibetans were circling the stupa, keeping it on their right side; some had prayer wheels, others were turning the prayer wheels that were set in the wall all the way around. We circled a couple of times and went through a narrow passage on the opposite side from the road and came out on a path through the rice fields. After a few minutes walk we found John’s house where we were going to stay.

Between two of them an opening lead in to the gigantic stupa whose golden upper part was decorated with the serene eyes of the Buddha. The stupa was surrounded by one circle of houses, and this was the whole town of Bodhanath. Monks and nuns and lay Tibetans were circling the stupa, keeping it on their right side; some had prayer wheels, others were turning the prayer wheels that were set in the wall all the way around. We circled a couple of times and went through a narrow passage on the opposite side from the road and came out on a path through the rice fields. After a few minutes walk we found John’s house where we were going to stay.Looking from the house, away from the stupa towards the mountains in the north, there was a small hill with a flat top with two great trees. Just as Sidi Ali had called me when I was in Meknès, this hill called me now, and one day, when I was smoothly coming down from an acid-trip, I obeyed the call. With brisk energy I completed the half hour walk up there before the sunset. I sat by a small shrine on the west side and saw the sun set behind the glittering golden towers of Katmandu showing the hill of Swayambunath in silhouette. Before leaving I looked around. There was a marvelous view of the whole valley from the top of the hill, and on the south side I found a half open gate, through which I spied an old house, hiding behind tall hedges.

Saturday, July 15, 2006

Friday, July 14, 2006

Thursday, July 13, 2006

JOURNEY TO THE EAST 5

My days in Inderpuri were scheduled down to the minute, with four daily meditation periods and two visits to the ashram, where Swamiji would talk, answer questions, and do a short meditation. One time, when I entered an unusually deep state of meditation, Swamiji extended the time till just after I came out of my blissful state. I had no doubt about his powers, but there were still things about him that bothered me. For instance I never heard him admit that any other being had reached a state of enlightenment comparable to his own, including the Buddha. And then there was something else. My friend Nick came by with his girlfriend Lena and with Tove, his mother, and when the two women told me of their private meetings with Swamiji they both independently looked beatified and said: “He set me in his lap!”

“He never set me in his lap,” I thought.

He recommended strict celibacy, and the couples who became his disciples all gave up their sex life. Years later it came out that he had slept with many of the young women. He was not the only guru who slept with his disciples, but it seemed to me that he was extra hypocritical about it. It caused a scandal and many disciples left. I definitely had a suspicion, but never the less I had a very high time the four months I was in Inderpuri.

Only it could not last.

My visa had been extended once, and when it expired again I had to leave. I decided to go to Nepal for a short while and then come back on a new visa. When I said good-bye to Swamiji his last words were: “Beware of Tantrics!” As it turned out, not knowing that the Tibetans were Tantrics, I became involved with them, and didn’t return to Swamiji.

When I saw him again, much later, on his first visit to Denmark, he treated me like he had never seen me before; he didn’t forgive me that I had neglected his advice and hadn’t come back.

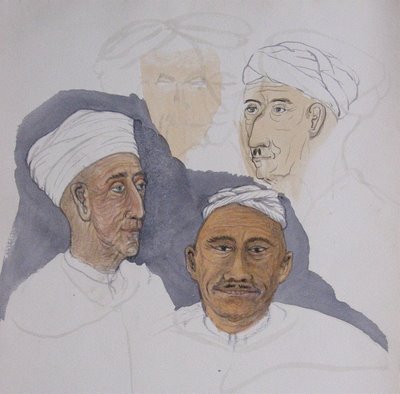

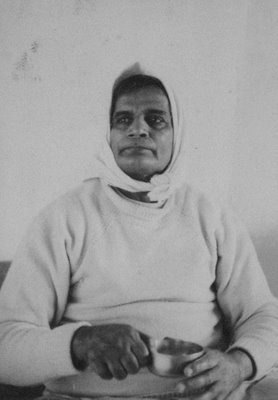

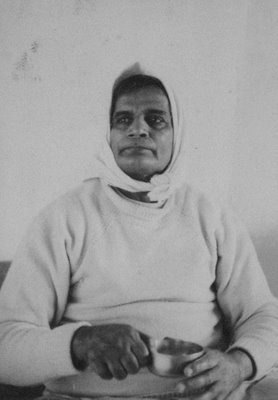

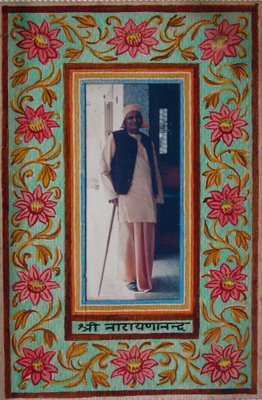

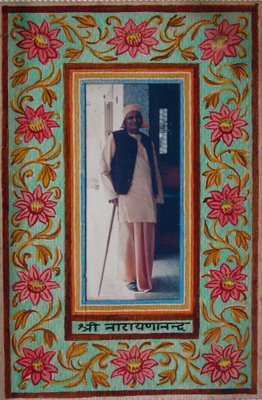

Swami Narayanananda

Swami Narayanananda

“He never set me in his lap,” I thought.

He recommended strict celibacy, and the couples who became his disciples all gave up their sex life. Years later it came out that he had slept with many of the young women. He was not the only guru who slept with his disciples, but it seemed to me that he was extra hypocritical about it. It caused a scandal and many disciples left. I definitely had a suspicion, but never the less I had a very high time the four months I was in Inderpuri.

Only it could not last.

My visa had been extended once, and when it expired again I had to leave. I decided to go to Nepal for a short while and then come back on a new visa. When I said good-bye to Swamiji his last words were: “Beware of Tantrics!” As it turned out, not knowing that the Tibetans were Tantrics, I became involved with them, and didn’t return to Swamiji.

When I saw him again, much later, on his first visit to Denmark, he treated me like he had never seen me before; he didn’t forgive me that I had neglected his advice and hadn’t come back.

Swami Narayanananda

Swami Narayanananda

Wednesday, July 12, 2006

Tuesday, July 11, 2006

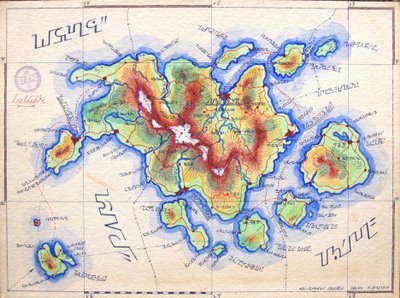

Template for Guru Rimpoche

Sunday, July 09, 2006

JOURNEY TO THE EAST 4

Several of my Danish friends were disciples of Swami Narayanananda and I wanted to check him out. He had his ashram in a newly build section called Inderpuri, just out of New Delhi. Jytte was there, and Niller was there too, all dressed in white, and he explained how to go about it. On the ground floor of the ashram was the meditation room, and the Swami was sitting on a dais right inside the door. It was a tricky screen door, if you let go of it, it would slam closed behind you with a disconcerting sound like a shot, just as you were bowing to the holy man. I had been warned and closed it silently before greeting the Swami.

I could not doubt that this was a man of great power. He received me graciously while scrutinizing me with his intensely beautiful eyes that seemed to radiate love. I decided to stay for a while.

I found a room that I could move into in ten days time and decided in the meantime to go with a young Danish sadhu, John, on a trip to Rishikesh, a town of ashrams situated where the Ganges comes out of the mountains. Only sadhus are allowed to live in the town; the merchants have to go away at night. John said he knew of a place where we could stay as long as we wanted. It turned out to mean that he knew how to get the door open to a hut belonging to one of the big ashrams. We were sadhus, but even so the time for a visit to an ashram was limited to three days.

Wandering around among the ashrams, we were invited in at one place and offered tea, and they told us to come back next day for the celebration of the guru’s birthday. For this celebration, about three hundred people came. It was a mixed crowd with all from half naked sadhus smeared with ashes to New Delhi businessmen in suits with their obese wives in silken saris. We were seated in long rows on the ground and provided with plates made of leaves stuck together with toothpicks. The guru himself and his disciples served us, and with a grin the guru gave John and me extra big servings of sweetmeats.

At one side was an altar with pictures and flowers. Half way during the meal a sadhu arrived in only a loincloth and with his long matted hair wound into a crown on his head. He was conducted to the altar by the guru and installed there among the flowers, where he sat with a beatific expression without eating anything. One moment our eyes locked together; with a tiny smile and without words he invited me: “Here is your chance! Give up everything and come with me.” But I was not ready to go naked into the mountains.

Next day a young sadhu came and sat on ‘our’ porch. We offered him food and smoked with him, and he stayed the night. In the morning he had his little fire going and went through the ritual of smearing himself with ashes, and we offered him again food and smoke; it began to look like he was going to stay. After a couple of days John was tired of him and told him to leave, but the karmic retribution was swift; the morning after evicting the sadhu we were evicted ourselves. I was ready to go back to Inderpuri, but John wanted to stay. Before I left he offered me a lump of hash, but since I was to begin my ascetic life with Swami Narayanananda I declined. That turned out to be lucky, for at one bus stop near Delhi the police spotted me in the bus and came rushing in to search all my belongings. They had obviously been sure of a catch when they saw a hippie sadhu, and they retired crestfallen, excusing their behavior, since I had proven to be a serious sadhu, a man of God!

I could not doubt that this was a man of great power. He received me graciously while scrutinizing me with his intensely beautiful eyes that seemed to radiate love. I decided to stay for a while.

I found a room that I could move into in ten days time and decided in the meantime to go with a young Danish sadhu, John, on a trip to Rishikesh, a town of ashrams situated where the Ganges comes out of the mountains. Only sadhus are allowed to live in the town; the merchants have to go away at night. John said he knew of a place where we could stay as long as we wanted. It turned out to mean that he knew how to get the door open to a hut belonging to one of the big ashrams. We were sadhus, but even so the time for a visit to an ashram was limited to three days.

Wandering around among the ashrams, we were invited in at one place and offered tea, and they told us to come back next day for the celebration of the guru’s birthday. For this celebration, about three hundred people came. It was a mixed crowd with all from half naked sadhus smeared with ashes to New Delhi businessmen in suits with their obese wives in silken saris. We were seated in long rows on the ground and provided with plates made of leaves stuck together with toothpicks. The guru himself and his disciples served us, and with a grin the guru gave John and me extra big servings of sweetmeats.

At one side was an altar with pictures and flowers. Half way during the meal a sadhu arrived in only a loincloth and with his long matted hair wound into a crown on his head. He was conducted to the altar by the guru and installed there among the flowers, where he sat with a beatific expression without eating anything. One moment our eyes locked together; with a tiny smile and without words he invited me: “Here is your chance! Give up everything and come with me.” But I was not ready to go naked into the mountains.

Next day a young sadhu came and sat on ‘our’ porch. We offered him food and smoked with him, and he stayed the night. In the morning he had his little fire going and went through the ritual of smearing himself with ashes, and we offered him again food and smoke; it began to look like he was going to stay. After a couple of days John was tired of him and told him to leave, but the karmic retribution was swift; the morning after evicting the sadhu we were evicted ourselves. I was ready to go back to Inderpuri, but John wanted to stay. Before I left he offered me a lump of hash, but since I was to begin my ascetic life with Swami Narayanananda I declined. That turned out to be lucky, for at one bus stop near Delhi the police spotted me in the bus and came rushing in to search all my belongings. They had obviously been sure of a catch when they saw a hippie sadhu, and they retired crestfallen, excusing their behavior, since I had proven to be a serious sadhu, a man of God!

Friday, July 07, 2006

Thursday, July 06, 2006

Wednesday, July 05, 2006

JOURNEY TO THE EAST 3

(Scroll down to read the first two accounts of The Journey to the East)

After two weeks in Herat we went to Kandahar. Here Ananda got sick and couldn’t hold anything in. I was frightened, one night he looked so thin and greenish that I thought he might die. I remembered how I had heard that prechewed food was the most digestible, and I asked Gisela if she would mind me chewing food for him, and she said that was OK with her. Next morning, as I cut me a piece of bread in the room where he was lying, he started screaming. It was like he knew what was in my mind and I chewed some bread thoroughly and gave it to him. He sucked it off my finger eagerly and then screamed for more. I chewed and fed him until he was satisfied and from that moment his recovery was rapid.

We made an excursion to a shady park next to a dry riverbed. I took acid there and was sitting in meditation when I felt an urge to open my eyes. I front of me stood a half circle of Afghans, all looking at me. I was stunned for a moment, but then I smiled and immediately they smiled back and with signs invited me to join them. I sat with them around a big red Afghan rug, just like the one in my childhood home. They were good to be with, no trips, no words necessary, just this row of shining black eyes and friendly smiles.

In Kabul I spend hours everyday in the hotel’s pleasant garden working on my translation. It is strange to think how this place of medieval peace a few years later was brutally catapulted into the twentieth century, in a war that forever destroyed the old Afghanistan.

We left Kabul after two weeks and went through the Kyber pass to Pakistan. Now Mother India was calling strongly, and we didn’t tarry in Pakistan. At the Indian frontier the Pakistani police officer found fault with Jytte’s passport, but we had learned to be philosophical about that kind of problems. We sat down, tea was ordered, and soon we were on friendly terms. After half an hour the police officer was satisfied; he took Jytte’s passport and stamped it without any commentary, and we were free to cross the border.

I don’t know how much of the exhilaration was due to the fact that we finally had reached the goal of our voyage, how much due to the actual atmosphere of the place, but I remember the feeling of relaxing into the embrace of this mild countryside as we walked towards the little border town. From there we went to New Delhi, and my first destination was my friend Fut (picture), whom I had originally planned to go to India with. He had preceded me and was now living in an ashram in the Himalayan foothills by Nanital. Niller and Sander wanted to come with me, while the women had their own plans.

Arrived in Nanital we asked for directions and were pointed to a mountain ridge: up there over the edge. The boys set out in a brisk tempo and were soon lost from sight. I took it step by step, slowly, and before I reached the top I came upon the two, panting and exhausted, taking a rest. The impetuosity of youth! As it were, they went down the mountain the very next day, and Sander I didn’t see again in India.

Arrived in Nanital we asked for directions and were pointed to a mountain ridge: up there over the edge. The boys set out in a brisk tempo and were soon lost from sight. I took it step by step, slowly, and before I reached the top I came upon the two, panting and exhausted, taking a rest. The impetuosity of youth! As it were, they went down the mountain the very next day, and Sander I didn’t see again in India.

Fut’s ashram had a great view of the Himalayan range, and his guru welcomed me eagerly - a little too eagerly for my taste! He had great plans for enlarging his ashram to receive more Westerners; it smelled of money more than of the Spirit. I decided it was not what I was looking for, and after having rested for a couple of weeks after the hardships of traveling, I took leave of Fut and his scheming guru and returned to New Delhi.

After two weeks in Herat we went to Kandahar. Here Ananda got sick and couldn’t hold anything in. I was frightened, one night he looked so thin and greenish that I thought he might die. I remembered how I had heard that prechewed food was the most digestible, and I asked Gisela if she would mind me chewing food for him, and she said that was OK with her. Next morning, as I cut me a piece of bread in the room where he was lying, he started screaming. It was like he knew what was in my mind and I chewed some bread thoroughly and gave it to him. He sucked it off my finger eagerly and then screamed for more. I chewed and fed him until he was satisfied and from that moment his recovery was rapid.

We made an excursion to a shady park next to a dry riverbed. I took acid there and was sitting in meditation when I felt an urge to open my eyes. I front of me stood a half circle of Afghans, all looking at me. I was stunned for a moment, but then I smiled and immediately they smiled back and with signs invited me to join them. I sat with them around a big red Afghan rug, just like the one in my childhood home. They were good to be with, no trips, no words necessary, just this row of shining black eyes and friendly smiles.

In Kabul I spend hours everyday in the hotel’s pleasant garden working on my translation. It is strange to think how this place of medieval peace a few years later was brutally catapulted into the twentieth century, in a war that forever destroyed the old Afghanistan.

We left Kabul after two weeks and went through the Kyber pass to Pakistan. Now Mother India was calling strongly, and we didn’t tarry in Pakistan. At the Indian frontier the Pakistani police officer found fault with Jytte’s passport, but we had learned to be philosophical about that kind of problems. We sat down, tea was ordered, and soon we were on friendly terms. After half an hour the police officer was satisfied; he took Jytte’s passport and stamped it without any commentary, and we were free to cross the border.

I don’t know how much of the exhilaration was due to the fact that we finally had reached the goal of our voyage, how much due to the actual atmosphere of the place, but I remember the feeling of relaxing into the embrace of this mild countryside as we walked towards the little border town. From there we went to New Delhi, and my first destination was my friend Fut (picture), whom I had originally planned to go to India with. He had preceded me and was now living in an ashram in the Himalayan foothills by Nanital. Niller and Sander wanted to come with me, while the women had their own plans.

Arrived in Nanital we asked for directions and were pointed to a mountain ridge: up there over the edge. The boys set out in a brisk tempo and were soon lost from sight. I took it step by step, slowly, and before I reached the top I came upon the two, panting and exhausted, taking a rest. The impetuosity of youth! As it were, they went down the mountain the very next day, and Sander I didn’t see again in India.

Arrived in Nanital we asked for directions and were pointed to a mountain ridge: up there over the edge. The boys set out in a brisk tempo and were soon lost from sight. I took it step by step, slowly, and before I reached the top I came upon the two, panting and exhausted, taking a rest. The impetuosity of youth! As it were, they went down the mountain the very next day, and Sander I didn’t see again in India.Fut’s ashram had a great view of the Himalayan range, and his guru welcomed me eagerly - a little too eagerly for my taste! He had great plans for enlarging his ashram to receive more Westerners; it smelled of money more than of the Spirit. I decided it was not what I was looking for, and after having rested for a couple of weeks after the hardships of traveling, I took leave of Fut and his scheming guru and returned to New Delhi.

Tuesday, July 04, 2006

Monday, July 03, 2006

Sunday, July 02, 2006

Saturday, July 01, 2006

JOURNEY TO THE EAST 2

In Iran it was not advisable to smoke. We were clean; not taking any risks, and went directly through on busses with only the necessary stops in Teheran and Mashad. When we arrived at the longed for border of Afghanistan, it was past closing time. It was the night of the full moon, two weeks after our departure, and the frontier guards offered us smoke, so that when I bedded down outside the frontier post I was immensely high and happy. I discovered that I could change my perception at will, back and forth between a picture and a pattern, whether my eyes were open or closed.

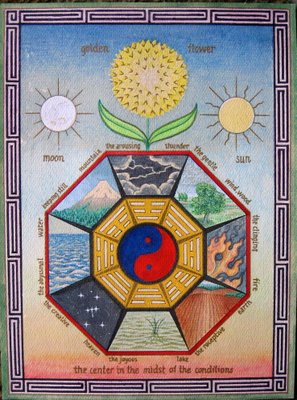

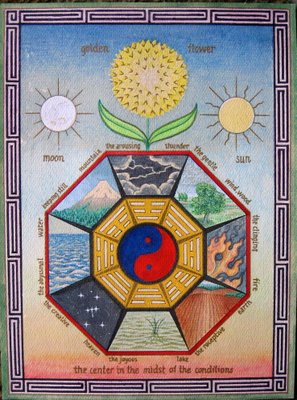

We stayed two weeks in Herat. Most transportation seemed to be by horse drawn gigs, and since all the horses wore small bells there was a constant tinkling in the air. We began to make acquaintance with other travelers that we had already seen here and there on the way. For work, I had brought with me another book to translate: The Secret of the Golden Flower. I like translating because one is forced to penetrate the text with deep understanding. For the same reason it is only a few special books I would want to translate. The pleasant balance between social life and inspiring work continued.

I took long walks around; Herat was not so much a town as a big village. One day I heard music with drums and by following the sound I came to a house. From the outside it was just a long wall with a gate in the middle, but as I reached the gate people came out and asked me in for a wedding. Inside was a big courtyard with musicians, dancers, and guests. In one end there was an open porch where the bride and groom and the close family were seated. I was given food and then invited to queue up outside a small room in a corner. It contained an enormous water pipe that a little old guy was firing up with much coughing. The queue moved in and each one took a hit and went back out to join the end of the queue, so that the queue became a circle that continued until the pipe was finished. Now the master dancer challenged me to dance, and I locked onto him. I was able to follow him step for step, and he got wilder and wilder and finally tore his shirt off, but that I didn’t want to follow because I didn’t want to show my money belt. The dance was over, but everybody was satisfied, and I was offered food before I left.

We stayed two weeks in Herat. Most transportation seemed to be by horse drawn gigs, and since all the horses wore small bells there was a constant tinkling in the air. We began to make acquaintance with other travelers that we had already seen here and there on the way. For work, I had brought with me another book to translate: The Secret of the Golden Flower. I like translating because one is forced to penetrate the text with deep understanding. For the same reason it is only a few special books I would want to translate. The pleasant balance between social life and inspiring work continued.

I took long walks around; Herat was not so much a town as a big village. One day I heard music with drums and by following the sound I came to a house. From the outside it was just a long wall with a gate in the middle, but as I reached the gate people came out and asked me in for a wedding. Inside was a big courtyard with musicians, dancers, and guests. In one end there was an open porch where the bride and groom and the close family were seated. I was given food and then invited to queue up outside a small room in a corner. It contained an enormous water pipe that a little old guy was firing up with much coughing. The queue moved in and each one took a hit and went back out to join the end of the queue, so that the queue became a circle that continued until the pipe was finished. Now the master dancer challenged me to dance, and I locked onto him. I was able to follow him step for step, and he got wilder and wilder and finally tore his shirt off, but that I didn’t want to follow because I didn’t want to show my money belt. The dance was over, but everybody was satisfied, and I was offered food before I left.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)